Theoryland Resources

WoT Interview Search

Search the most comprehensive database of interviews and book signings from Robert Jordan, Brandon Sanderson and the rest of Team Jordan.

Wheel of Time News

An Hour With Harriet

2012-04-30: I had the great pleasure of speaking with Harriet McDougal Rigney about her life. She's an amazing talent and person and it will take you less than an hour to agree.

The Bell Tolls

2012-04-24: Some thoughts I had during JordanCon4 and the upcoming conclusion of "The Wheel of Time."

Theoryland Community

Members: 7653

Logged In (0):

Newest Members:johnroserking, petermorris, johnadanbvv, AndrewHB, jofwu, Salemcat1, Dhakatimesnews, amazingz, Sasooner, Hasib123,

Theoryland Tweets

WoT Interview Search

Home | Interview Database

Your search for the tag 'comics' yielded 10 results

-

1

Interview: Mar 8th, 2005

Comic Book Resources Interview (Verbatim)CBR

Jordan's been a long time fan of comics and graphic novels, dating back to his early childhood when his family first exposed him to comics.Robert Jordan

"I learned to read early—I was reading Jules Verne and Mark Twain at five—and my Uncles went into their attics and gave me not only their old "boys' books," things like Jack Armstrong: All-American Boy and The Flying Midshipmen, but also old comics they had from the '30s and '40s. For a while, I had a fairly valuable collection, though I didn't know it then. None of the really rare items, but some that would have fetched nice prices. Though I have to admit that after all these years, I can't recall the issue numbers. I bought, too, choosing carefully because my allowance only stretched so far. My own purchases were pretty far ranging. For example, I liked Batman and Scrooge McDuck about equally. In any case, that ended when I went away to college.

"I came home for the first time to find out that my mother had given all of the comics and boys' books to various children because 'surely I didn't want those old things any more.' There's no way you can go to a ten-year old and tell him you want him to give back the comics he was just given. I mean, they weren't that valuable. But I still followed comics, and later graphic novels, which didn't exist when I was in college. It was really intermittent—'Howard the Duck,' Chaykin's 'American Flagg,' a few others that I still have—until Frank Miller got his hands on Batman. That brought me back on board, and I've been there ever since. I'm pretty choosy, partly as a matter of time—most of my reading is print—but when I see something that's new and interesting, I leap on it. And I buy compilations of older works that I recall fondly, too, for myself and as gifts. My wife doesn't know it, but she was a fan of Plastic Man as a girl, and she's getting six hardcover volumes of 'Plastic Man' compilations as soon they're delivered."

Tags

-

2

Interview: Sep 7th, 2009

Christian Lindke

Now, you've talked briefly—I mean, jeez, you've got so much in that conversation that I'd like to jump off from...

Brandon Sanderson

Sorry, I'm very verbose, so feel free to cut in any time.

CHRISTIAN LINDKE

...involved in thing that you did, I mean...I was thinking earlier in your comments about how those who came to start reading science fiction and fantasy in the, you know, 80s, largely—in the post-Lin Carter boom of fantasy and science fiction that came out in the late 70s, early 80s...

BRANDON SANDERSON

Mmhmm.

CHRISTIAN LINDKE

...being primarily people who read novels rather than short stories—and the first thing that hit my mind is that, you know, kind of one of the seminal works of science fiction, right—Asimov's Foundation—BRANDON SANDERSON

Yep.

CHRISTIAN LINDKE

There's a whole generation of people older than I am, and older than you are, who read that as short stories as they came out...

BRANDON SANDERSON

Yep. Yep, and I read it as a novel first; I'd never known it in short story form.

CHRISTIAN LINDKE

Right, and I'm in the same boat, and those even seem, you know, like short novels to me.

BRANDON SANDERSON

Yep.

CHRISTIAN LINDKE

You know, those are the kind of books you read in an afternoon, where a Tad Williams novel is something that might take, you know, a weekend of, you know, devoted reading...

BRANDON SANDERSON

Yup.

CHRISTIAN LINDKE

...ah, to get through the Bible-thin pages, and the massive length of the novel has become the norm—or an Ian Banks science fiction novel...

BRANDON SANDERSON

Yup.

CHRISTIAN LINDKE

...which, you know, if you bought in hardback, you could probably, you know, put a hole in the floor when you set it down...

BRANDON SANDERSON

[laughs] Yeah.

CHRISTIAN LINDKE

...it's so weighty. But, I wanted to, since you talked a little bit about internet distribution, and, you know, the kind of expectation of 'free', but also the interactivity on something that maybe, you're not using it as a means to actually distribute, but maybe to work and foment the product. You worked on your more recent Warbreaker novel through a kind of, we'll say, sausage-making process that, if people followed it on the internet, they could see the development of the novel before it was published.

BRANDON SANDERSON

Yes.

CHRISTIAN LINDKE

Could you about that a little bit?

BRANDON SANDERSON

Sure.

CHRISTIAN LINDKE

And kind of the impetus behind that and, you know, how you feel about the result of that process.

BRANDON SANDERSON

The impetus behind it was really watching how the internet worked with viral marketing and with really the self-made artists—the webcomic community, I pay a lot of attention to, because of how I think it's fascinating the way that this entire community of artists is building up and bypassing all middlemen, and just becoming...you know, I have several friends who are full-time cartoonists who can make their entire living posting webcomics through ad-supported and reader-supported—you know, either buying collections or donations and things like this—I thought that's fascinating. I don't think that it will work, as I said, with long-form or even short-form fiction because of the difference between the mediums, but I like looking at webcomics as a model just to see what's going on there. There's a science fiction author, Cory Doctorow, who's a very interesting author and has a lot of very fascinating things to say, a lot of them very, uh...very...aggressive, and certainly conversation-inspiring—how about that?—and one of the things he started doing, very high-profilely—he's one of the bloggers of Boing-Boing, so he's very high profile on the internet—is that he started posting the full text of his books online as he released them with his publisher. So, Cory Doctorow is releasing his books for free, and he has a famous quote, at least among writers, which says that, "As a new author, my biggest hindrance—the biggest thing I need to overcome—is obscurity."

And, so that's why he releases his books for free. He figures, get them out there, get as many people reading them as possible...and then that will make a name for him, and this sort of thing. Well, that scares a lot of the old guard. Giving it away for free is very frightening to them, and for legitimate reasons, but there was a whole blow-up in the Science Fiction Writers of America on this same topic, about a year or so ago—what you give away for free, and what you don't—and I said that Cory was right in a lot of the things that he was saying, particularly about obscurity. There are so many new authors out there. Who are you going to try, and how are you going to know if they're worth plopping this money down? It's the same sort of problem I have with albums. I don't want to try a new artist, because if I plop $10 down and then hate every track on the album...what's...what have I just, you know, done? I feel like I've wasted the money; I feel annoyed. So, I either wait till I get recommendations—and even then, a lot of times I'll buy an album, and then be like, "Man, I wish I'd gotten something else."—or I'll try the really popular songs, which may not be the songs on the album I like, which just puts you in all sorts of problems where, how do you know if you're going to like this artist or not?

Authors are the same way. You pick up a fantasy novel—a big, thick 600-page fantasy novel—you look at it, and you say, "You know, how am I gonna know if this guy's any good?" Am I gonna spend 30 bucks on a hardcover, or even, you know, 8 or 9 bucks on a paperback, you get home, and then you start reading this and you discover that this is just the wrong artist for me? So, I felt that the thing to do was to release a book for free. Being, just, I dunno...[cut] part of it was wanted to do the [?], try something I hadn't seen before, which was to write the book, and post the drafts online as I wrote them, chapter by chapter, perhaps hopefully to get a little publicity, where people would say, "Hey, he's letting us see the process!" Partially to, you know, to give something to my fans that they couldn't get from other books, which is being able to see the process firsthand, help out new writers, whatever...whatever it could do, I felt very good about the opportunity there, and posting chapters as I wrote them, always with the understanding that this would be the next book I published; I mean Tor had already said that they were going to publish it. It wasn't an experiment in that I wanted to see how it would turn out—I was pretty confident in the story, with the outline I had—but I wanted to experiment in showing readers drafts, letting them give me advice, essentially workshopping it with my readers as I wrote it, and see how that affected the process, and affected the story.

And so that's what I did, and actually I started posting drafts in 2006; it didn't come out until 2009, so it was a three-year process during which I finished the first draft after about a year of posting chapters, and then I did a revision, and then another revision, and they got to see these revisions, and I would post um...you can still find them on my website—brandonsanderson.com—you can still find all of these drafts, and comparisons between them using Microsoft Word's 'compare document' function, and some of these things, and...I think it was a very interesting process. Did it boost my sales? I don't know. Did it hurt my sales? I don't know. It was what it was, and it was a fun experiment; it's something I might do again in the future. Probably if I write a sequel to Warbreaker, I would approach it the same way. It's not something I plan to do with all of my books, partially because not all of my books do I want the rough drafts to be seen. Warbreaker, I was very...I had...I was very confident in the story I was telling, and sometimes, parts of the story you're very confident in, and parts of the story you know you're going to have to work out in drafts, and that's just how it is, and in other cases, it's better to build suspense for what's happening, and...so, there's just lots of different reasons to do things, but Warbreaker, being a standalone novel that I had a very solid outline for was something that I wanted to try this with, and once the Wheel of Time deal happened, which was just an enormous change in direction for my career, I was very glad I had a free novel on the internet, because then, people who had only heard of me because, "Who's this Brandon Sanderson guy? I've never heard of him before," could come to my website, download a free book, read something that I'd written, and say, "Okay," then at least they know who I am. They at least have an experience—and hopefully they enjoy the book, and it will put to ease some of their worries, even though Warbreaker isn't in the same style that I'm writing the Wheel of Time book in, it at least hopefully can show that I can construct a story and have compelling characters and have some interesting dialogue and these sorts of things that will maybe, hopefully, relax some of the Wheel of Time fans who are worried about the future of their favorite series. [chuckle in background]

CHRISTIAN LINDKE

Right, and it's good that you're working with Tor in a lot of this, because of course Tor is one of the publishers that's kind of renown for attempting to—I mean I don't know, I don't get to look at the numbers either, so I don't know what their success is—but really attempting to get readers to purchase their books, and to read their books, and then purchase follow-up books by, you know, almost using a 'first one is free' philosophy on the internet.

BRANDON SANDERSON

Yeah, Tor is very good at that. In fact the whole science fiction and fantasy market has been very good—as opposed to the music industry—in using the internet and viral sorts of things to their advantage rather than alienating their audience, which I appreciate very much.

CHRISTIAN LINDKE

Yeah, I mean, obviously the music industry has a disadvantage that the publishing industry in books doesn't suffer from, and that's the brevity of the item.

BRANDON SANDERSON

Yep, yep. Very easy to download a song, and...yeah.

CHRISTIAN LINDKE

And they have some additional obstacles, but it's, you know, one of the things that they've done extraordinarily poorly is handle any kind of PR, or any kind of the public debate as far as, you know, defending themselves I think against—you know, legitimately it's theft, taking music for free—but, you know, attacking twelve-year-olds...

BRANDON SANDERSON

Right. Or grandmothers, or things like that. Yeah, just a [?] way to approach it. You know, they're just a very different sort of situation. With audio, number one, downloading a song and listening to it, you get the very same experience listening to it that you would if you'd bought it, whereas downloading a book, it's not the same experience; reading it electronically for most of us is not the same experience as holding the book. And beyond that, publishing in today's market is actually kind of a niche thing; it's a niche market. Not entirely of course, but science fiction and fantasy, we are...we have...despite the explosion of science fiction and fantasy into the mainstream, I still think we are a small but significant player in publishing, if that makes sense. We have a small fanbase that is very loyal that buys lots of books, is generally how we approach it, and because of that loyal fanbase, that's really how science fiction and fantasy exists as a genre, because of people who are willing to buy the books when they can go to the library and get them for free, people who want to have the books themselves, to collect them, to share them, to loan them out. That's how this industry survives, hands down. And so, I mean...that's...Tor gets by. The reason Tor can exist as a publisher is because it produces nice, hardcover epic fantasy and science fiction books that readers want to own and have hardcover copies up to display on the shelves, with nice maps, with nice cover illustrations, which, you know, covers on science fiction and fantasy books have come a long way since the 60s and 70s. Just go back and look at some of these...and part of that is because the artists of course have gotten better—there's more money in it—but there's also this idea that we need to create a product that is just beautiful for your shelf, because that's how we exist as an industry. Romance novels don't exist on the same...in the same way; they exist in lots of volume of cheap copies being sold, and romance authors do very well with paperbacks—and some science fiction and fantasy authors do too, just different styles—but with epic fantasy, we really depend on those very nice, good-looking hardcovers, and so, we....giving away the book for free actually makes a lot of sense for us, because...the idea...we're selling for the people who want to have copies anyway, who could've gotten it for free from their friends, or by going to the library and getting it, or now downloading it, I mean...we have a very literate community; they know where to find the book for free online if they want to get them illegally, and we don't really go and target those websites and take them down, because you know what....it's not...the people who are buying our books are not the people who are...how should I say? If they're gonna get them for free, it doesn't discourage them from buying the book, generally. In fact they're more likely, I think, to buy the book if they read it for free first, and then like it, we're the types of people...I mean, we're the types of people who have 5,000 books in their basements, who if they love a book, go buy it in hardcover, and if they just merely like a book, we go buy it in paperback, and loan it around to all our friends still.

And so, that's who we're selling to, and that's who I think we'll continue to sell to. I don't think the book industry is threatened by the internet in the same way that the movie and music industry is, for various reasons, but I also don't think that we can...a lot of people say, 'get rid of the middle man'. I talked about the webcomic industry, and how they're able to just produce it all themselves. It doesn't work with novels. What I think readers don't realize is that most of the cost in a novel is not the printing. Most of what you're paying for when you're buying a book is the illustrator, is the copy-editor and the editor, and the layout and design team and all of this, which you really can't get rid of. Bypassing the middleman means you'd get a book that's unedited, and if you've read a book that's unedited, you'll realize why we have editors and typesetters and all of these people, and so, you know, the Kindle Revolution, if it ever happens—the ebook revolution or this sort of thing—will actually, I think, be a benefit to us, but I think people are going to be surprised that the prices don't come down as drastically as they would've thought, because of that, you know, $25 hardcover, you know, $5 of that is printing and shipping, but most of that is overhead for the publisher.

CHRISTIAN LINDKE

Yeah, Lord knows I read the unedited version of Stranger in a Strange Land, and I said, "Oh god, give me the edited version again."

BRANDON SANDERSON

[laughs] Yeah.

Tags

-

3

Interview: Apr 21st, 2012

Matt Hatch

So after you had left the home, obviously your mother couldn't stop you from going to the drugstores to pick up those comics later on. What authors did you read in that genre?

Harriet McDougal

Well, I loved Stephen King, of course, and Ramsey Campbell. K.W. Jeter and I worked on some of his stuff, and he gave me credit for turning him around for horror, that that was what he should be writing. I haven't read any in a while. Tomorrow I'll wake up remembering lots of other names. And I also came out of childhood with a real love for cartoons and comics. My best friend's mother was very cute, and when I was nine, she would say now, "Explain this cartoon in The New Yorker to me." So I had this tremendous ego boo about cartoons. And I did edit cartoons—cartoon collections—at Tempo, and I loved that.

Matt Hatch

What were your favorite strips?

Harriet McDougal

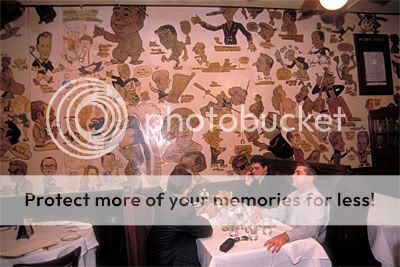

Well I loved Hagar the Horrible, which was new at that point, and Tempo had Beetle Bailey—that was the one that sold best and I paid the most for—and I liked the guy who was selling rights to King Features. At one point, we had a lunch that lasted a long time, and he called me the next morning. He said, "Harriet, did I leave a package with you at lunch?" And I said, "No, I'm sorry John; you didn't." And we were talking later, and I said, "Did you find that package you lost?" He said, "Yeah, I left it at my bookie's." (laughter) So anyway, then along comes the sell piece for Hagar the Horrible, to pitch the strip, and I called up—and I was supposed to go through a rigamarole getting approval for what I bought, and how much I was to spend—and I just called this guy up, and said, "John, I'll pay you what I'm paying for Beetle." And then I said I'd done it. Fire me; I don't care. And of course it was wonderful. And so Dik Browne came and called on me, and I said, "Oh hi, how nice to meet you!" And he said, "Well, nice to meet you! I have come to take you out!" And he took me to a wonderful—The Palm restaurant which was covered with drawings by cartoonists, that is they scrawled all over the plaster. It was fun, and I love cartoons.

Matt Hatch

Still today?

Harriet McDougal

Yeah, I do. I do.

Matt Hatch

I grew up on cartoons, and Hagar the Horrible.

Harriet McDougal

It's wonderful. Chris Browne isn't as good as his father was. It's okay, but not what it was.

Matt Hatch

I'm partial to Calvin and Hobbes.

Harriet McDougal

Yes! Absolutely. Bloom County?

Matt Hatch

My kids don't have the same appreciation any more, for cartoons. It's a different world. I mean, it's probably my fault, for not offering it to them...

Harriet McDougal

What, for not locking them in cages? (laughter) Times change.

Matt Hatch

Yeah, that's right. I mean, cartoons are different; they're 24/7 now, and we don't get a weekly newspaper...it's not the same.

Harriet McDougal

I like Pearls Before Swine. Do you get that? It's a newspaper strip. It's funny.

Matt Hatch

No. I'll have to look it up.

Tags

-

4

Interview: Mar 18th, 2013

Tom Doherty

Another great—and profitable—thing Harriet did for us was cartoons. She brought some great cartoons over to Tempo. In 1980, the very first year, we wouldn't actually have shipped any books, because it takes a while to get things organized and written. We'd just started incorporating late in '79. To get books out in 1980 would have been a challenge, but King Features had two movies that year: Flash Gordon and Popeye. We hadn't come up with the Tor imprint yet, but we rushed out tie‑ins for those movies, both in comic form and in novelization.

Harriet McDougal

Harum‑scarum. Conan with one hand and Popeye with the other. As the years went by, Tor grew and grew and grew. From my point of view, there came a year when Jim [James Oliver Rigney Jr., AKA Robert Jordan] was beginning to make some real money. I was commuting up to Tor for one week a month, every month. I had a TRS-80 machine with tape storage, and it would record the entire inventory of Tor books so nicely, but then I could never unload it when I got up here. It was a pretty miserable system. Then there came a year where I thought: "This is the year I could either add a third stress medication, or I could stop being editorial director of Tor." It was time to do that.

Tom Doherty

I hated every time she ever cut back. I understood, but I didn't like it.

Harriet McDougal

Well, I was doing a lot of editing. Heather Wood told me once, when she was working here, that I was editing a quarter of the hardcover list, which meant I was also handling a quarter of the paperback list because of the previous releases. It was a lot. But it was a great ride.

Tom Doherty

(To Irene Gallo) That was her problem for doing the best books.

Harriet McDougal

I don't know about that. But I loved working with Michael and Kathy Gear, Father Greeley, Carol Nelson Douglas. All manner of creature. Lots and lots of them.

Tom Doherty

Yeah. Andy [Greeley]'s books used to make the bestseller list back when you were editing him. That was fun. He came to us first with science fiction, right? Then we did a fantasy, with your editing. He loved your editing. We ended up doing all of his books.

Harriet McDougal

I really loved working with him.

Tom Doherty

You must have some stories like mine about Jerry Pournelle. What kind of crazy things happened to you in your early days? You were editing Fred Saberhagen, David Drake, people like that.

Harriet McDougal

They were just great to work with. Nobody was yelling and screaming down the phone at me.

Tom Doherty

Fred's Swords, the first three Books of Swords were bestsellers for us, too.

Harriet McDougal

They were good. I used to tease Fred about his day job as a pitcher in the professional baseball world. I think he'd heard that maybe too many times. "There was a Saberhagen pitching." "Saberhagen pitches shutout" and so on.

Tags

-

5

Interview: Sep 9th, 2010

TWOK Signing Report - HardcorePooka (Paraphrased)HardcorePooka

Also, while Brandon was signing my books and kindle I asked him a question. I asked if, as I know he is interested in webcomics and comics, if he would ever consider doing something along those lines with an artist.

Brandon Sanderson (paraphrased)

He answered that he had been working on something but neither he nor the artist thought it was going in the right direction, but that yes, he would hopefully be doing something along those lines at some point.

HardcorePooka

This made me very happy.

Tags

-

6

Interview: Jul 16th, 2013

Big Shiny Robot Interview: Brandon Sanderson (Verbatim)Dagobot

With so many superhero comics running for so long, did you ever run into problems with originality in writing the book?

Brandon Sanderson

Again, Steelheart is an action book. It deals less with the superhero tradition and more with the story of ordinary characters trying to take down Steelheart. Still, I am evoking some of those superhero concepts, so I did run into some of the issues you're talking about.

For example, I found that a lot of potential names for superheroes and super villains have been used a dozen times by DC or Marvel over the years, so coming up with original names was difficult. Finding original uses of powers was also very difficult for the same reason. I had to scratch into nooks and crannies to discover things I hadn't seen done extensively before.

I do enjoy the comic form, but&mdash'outside of some of the indies—I find I don't often get complete storylines in the way that I would like to. One of the things I want to do with Steelheart is to create a complete story with a distinct beginning, middle, and end. I do hope that I've been able to clear some new paths and add something distinctive to the genre. At the end of the day, though, I was just trying to tell an awesome story.

Tags

-

7

Interview: Jul 16th, 2013

Big Shiny Robot Interview: Brandon Sanderson (Verbatim)Dagobot

Some people may say that stories about superheroes are predominantly highly-colorful, action-packed, but most of all a visual experience—how can you get over this with a prose novel? What does prose bring to the table that "comics" can't—or don't?

Brandon Sanderson

Excellent question. I've thought about this quite a bit and have a few of my own theories about the novel as form. What can novels do that films can't? The trick is to highlight what a novel can do. For example, more so than in visual media, novels allow you to really dig into character thoughts, emotions, and motivations. Steelheart is told from the first-person viewpoint of the main character David. In doing that, I can really dig into who David is as a character and have the way he describes the world inform us about him. Granted, a good comic is going to give you some of this, but there just isn't a lot of space for words. The more thoughts you add in comics, the more the reader just wants you to move on with the story. There are different strengths to the different mediums of storytelling, but one of the strengths of the novel is its ability to showcase character.

Tags

-

8

Interview: 2011

Reddit 2011 (Non-WoT) (Verbatim)ktbrava (January 2011)

If we want our children to grow up smart, why do we send them mixed messages in cartoons saying that the villain is a genius and the hero beats them with brawn?

Brandon Sanderson ()

Asimov wrote an excellent essay on this very topic. In it, he spoke on the troubling history of the Sword and Sorcery genre, where a simple-minded, muscle-bound hero often would slay a crafty wizard. The essay, I believe, is called simply "Sword and Sorcery," and can be found in the collection titled MAGIC, which includes some of his fantasy stories and essays about fantasy.

Alas, Reddit, I couldn't find a copy of it on the internet for you to peruse.

Tags

-

9

Interview: Sep 23rd, 2013

Paul Goat Allen

Great answer. I have to be honest, Brandon. I'm not a big fan of superhero fiction—but Steelheart blew me away. I described it as a "mind-blowing" experience. Do you recall where the original seed of inspiration for this novel, and series, came from?

Brandon Sanderson

That's very cool to hear! Approaching this book was in some ways very difficult for me because I have read superhero prose, and it usually doesn't work. I came to it with some trepidation, asking myself, "Is this really something you want to try?" A lot of the superhero tropes from comic books work very well in their medium and then don't translate well to prose. So for my model I actually went to the recent superhero films. Great movies like The Dark Knight or The Avengers have been keeping some of the tropes that work really well narratively. Tropes that feel like they're too much part of tradition—like putting Wolverine in yellow spandex—work wonderfully in the comics. I love them there! But they don't translate really well to another medium.

I think part of the problem with superhero fiction is that it tries to be too meta. It tries very hard to poke fun at these tropes, trying to carry them over into fiction, and it ends up just being kind of a mess. But the genre has translated wonderfully well to film through adaptation. So when I approached Steelheart, I actually didn't tell myself, "I'm writing a superhero book." In fact, I've stayed very far away from that mentally and said, "I am writing an action-adventure suspense-thriller." I use some of the seeds from stories that I've loved to read, but really, Steelheart is an action thriller. I used that guide more than I used the superhero guide. I felt that adaption would be stronger for what I was doing. Comic books have done amazing things, but I felt this was what was right for this book.

As for the original seed that made me want to write this story, I was on book tour, driving a rental car up the East Coast when someone aggressively cut me off in traffic. I got very annoyed at this person, which is not something I normally do. I'm usually pretty easygoing, but this time I thought to myself, "Well, random person, it's a good thing I don't have super powers—because if I did, I'd totally blow your car off the road." Then I thought: "That's horrifying that I would even think of doing that to a random stranger!" Any time that I get horrified like that makes me realize that there's a story there somewhere. So I spent the rest of the drive thinking about what would really happen if I had super powers. Would I go out and be a hero, or would I just start doing whatever I wanted to? Would it be a good thing or a bad thing?

Tags